I am trying to remember when the name of this city first entered my consciousness in childhood. Niigata, the name of a place, along with Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Pearl Harbour, overheard in bits and pieces from the sidelines, in between spaces of mutterings, at the kitchen table maybe, or while watching Rememberance Day ceremonies on TV, something about a life before I was born. All I knew is these places were of particular significance to my father and our family.

This is my fourth time visiting Niigata, but the first time was forty years ago when I took the boat from Otaru in Hokkaido during my trip to Japan in 1983. I found a place on the map called the International Friendship Centre, or something like that, and went to find it.

There was a young woman working there, not much older than me, who spoke English. I told her my father was a Canadian POW in Niigata during World War Two and could she help me find out where the prison camp had been.

So began a friendship with Junko and a series of events which included my father returning to Japan, meeting with officials from the city and his writing a memoir of his experience which, I can only surmise, along with time, infused a painful memory of tremendous suffering with greater meaning and conciliation, and ultimately, forgiveness.

That day in 1983 Junko invited me back to stay with her parents which, when I think back, was such an act of kindness which didn’t seem at all extraordinary to me at the time. It does now. With Junko translating, we asked for more information about a prison camp without any answers. I’m ashamed to say I actually had the temerity to write my father and confirm whether he had the correct location. He didn’t take it well.

In his memoir, titled Guest of Hirohito, my father wrote that my letter prompted him to write city officials in Niigata, pointing out this seemingly forgotten piece of history. The city officials responded generously, inviting him to visit Niigata and discover with them, the former camp and work sites.

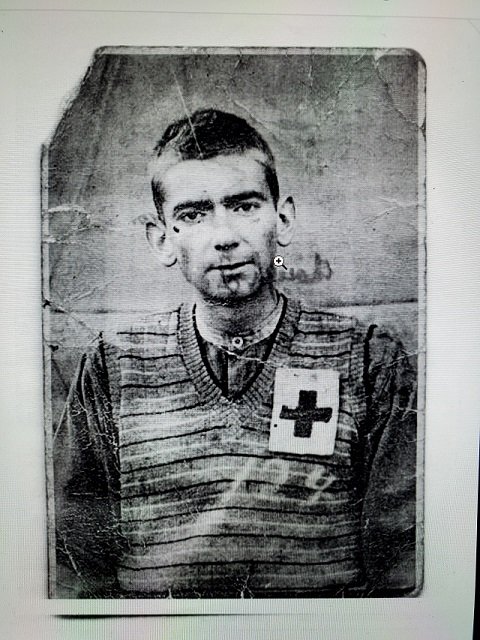

The Canadian soldiers were sent to Hong Kong in 1941 to defend the then British colony and after a fierce battle against the invading Japanese army, survivors were taken prisoner and eventually sent to Japan. My father made the surprising decision to visit Hong Kong for the first time since the war, and then Japan, taking the Niigata officials up on their offer.

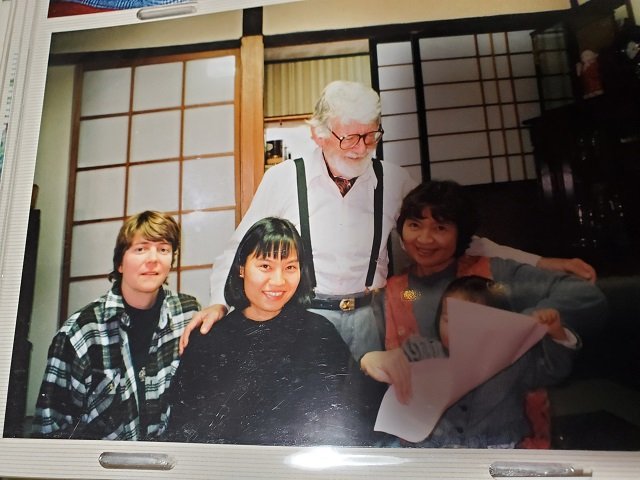

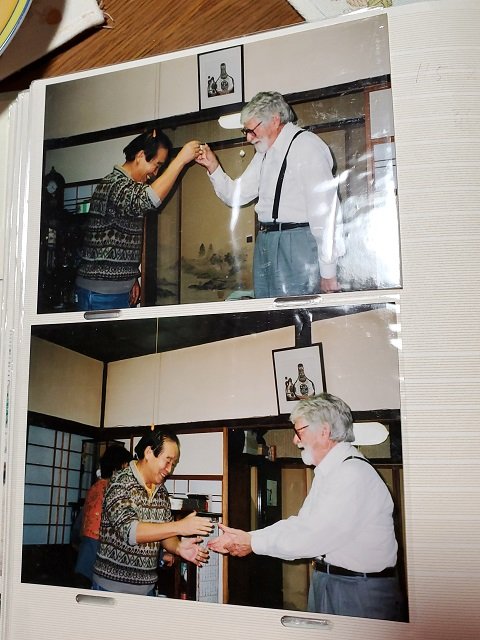

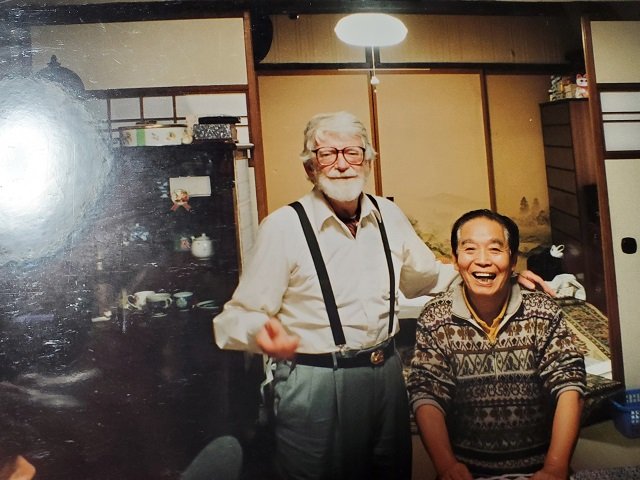

It was during this initial trip where my parents met Junko, as well as, Rieko, who translated for the official group (and who was a friend of Junko’s). They met Junko’s family and Rieko also came to visit my parents in Canada. Our whole family went to Niigata in 1995 to visit Junko’s family again, when Guest of Hirohito was published in Japanese, and I also visited one more time with my parents in 1998 when they were invited to be part of a ceremony to inaugurate a peace memorial in one of the city parks.

I can’t remember why I felt the need to visit Niigata, or the Friendship Center back in 1983. I don’t think I even mentioned to my parents I was planning to go there. Was it an attempt to partake in the powerful coalescence of wartime events and the personal experience of someone in your family? I still don’t know. Maybe because it lets the casualty of past suffering of a parent or family member become more real because you are in that very place where they suffered? Does that, in turn, make it acutely emotional and almost a release of some sort? Or is it the need, futile really, to try and understand something you may never know.

Niigata is lovely city, with the wide Shinano river flowing by. The weather was perfect and the air fresh. Today I rode my bicycle to the old site of the prison camp and the peace memorial. The old camp was long ago paved over and built up, I knew that, but it was important for me to visit, again, I don’t know why. But most of all, I’ve come to see Junko and Rieko, who were very fond of my parents and, even though we’ve spent such little time together, they seem like close friends you’ve known all your life. In a way, we have known each other, or, at least Junko and I have, for forty years.

Junko took me to visit her mother (her father passed away in 2007, then same year as mine) and she is healthy and active in her mid-eighties. We had tea and pineapple and persimmon, and she (through Junko) told me how shocking it was when I stayed with them and put soy sauce on my rice.

We had a good laugh and I was very embarrassed, because I’ve long since known what an odd thing it is to do in Japan; the soy sauce on rice episode was only one of the oddities I exhibited when staying in their home as a clueless twenty-one year old, but no one let on at the time. What I do remember is Junko and I drinking a lot of beer.

Junko’s mother had a photo album on hand of our previous visits, there was my dad and Junko’s father, who was also a POW of the Soviet army, arm in arm, singing some kind of wartime song. A lot of drinking occurred then, and it would happen again tonight. Off to dinner with Junko, on our bicycles, to meet Rieko and her partner, where we ate well, drank a lot of beer and rambled on about this and that.

In the last few years of his life, his brain riddled with Alzheimer’s, we lost the man we recognized as someone who was able to temper bitterness with love. Ken Cambon was not the only POW who returned to Japan and faced their demons there and were comforted by a warm reception from local people who recognized their suffering, and shared their own stories. What a catharsis for these former soldiers who survived to old age. Maybe it’s something I am also seeking.

As I write these words

Raindrops on the window pane

Much like my tears, fall